Magicube

This post was written for Indie Tsushin. Please check them out!

As creators, we find inspiration where we can. Just as much as we’re motivated by a new idea or concept, sometimes we’re simply inspired by wanting to have things look or sound a certain way. This is a form of communication expressed by Joseph White in PICO-8, which deliberately and purposefully “inhabits boundaries.”

So it’s a combination of identifying what’s already happening in the software world with tools like PuzzleScript and Twine. You know, things like this that have an identity that expresses itself in the work made with it. […] These tools—they have an implicit design manifesto built into them, and in PICO-8’s case […] the principles are that small things matter. You can make small things—they are valuable by themselves.

Limitations can work wonders for an artist: when constrained by technological or hardware restrictions, the added pressure comes together into something that could only exist on that system. Titles like the ridiculous DOOM de-make, POOM, presents visuals that push the PICO-8 to its limits. The previously-featured UCHU MEGA FIGHT delivers a fully-fledged fighting game, complete with combos, special moves, and more playable characters than the original Street Fighter II, somehow all squeezed into the strict size limits of a PICO-8 cartridge.

Other games, like Celeste and SlipWays, used the system’s simple and intuitive programming engine to make prototypes for games that would be fully-realised later on. The pixel-art precision platformer and interplanetary empire-planning puzzler would both outgrow their original homes to be extended far beyond these initial incarnations, with enhanced graphics, sound, and game play—but both were able to hammer out their cores thanks to the lightweight system forcing them to ensure tight, fun basics beforehand.

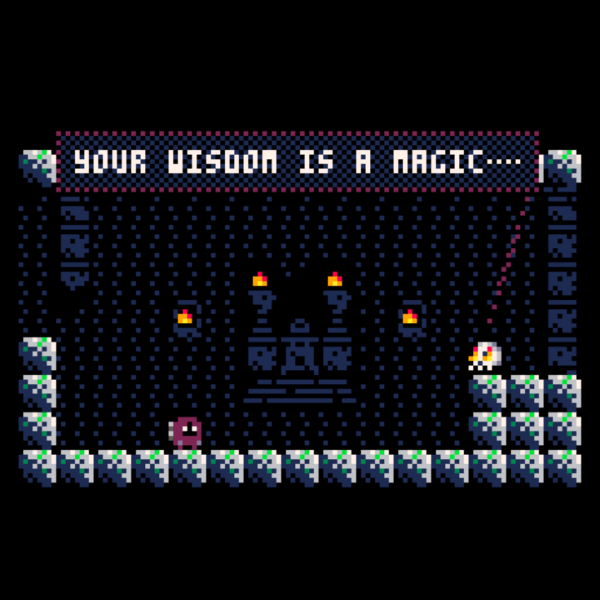

Magicube by nebu soku, on the other hand, feels like exactly the kind of game that PICO-8 was made for: minimalist in almost every sense of the word and all presented in a characteristic pixelated style. The controls are dead-simple—a perfect match for the fantasy-console’s NES-style control scheme; the background music feels like it fits hand-in-glove with PICO-8’s soundfont.

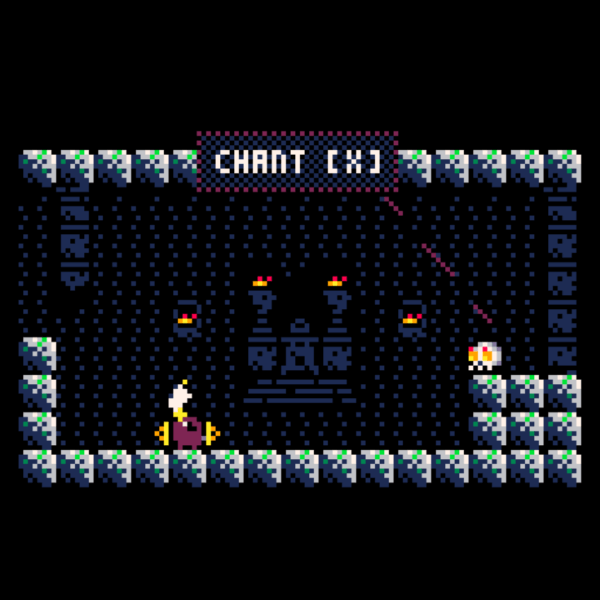

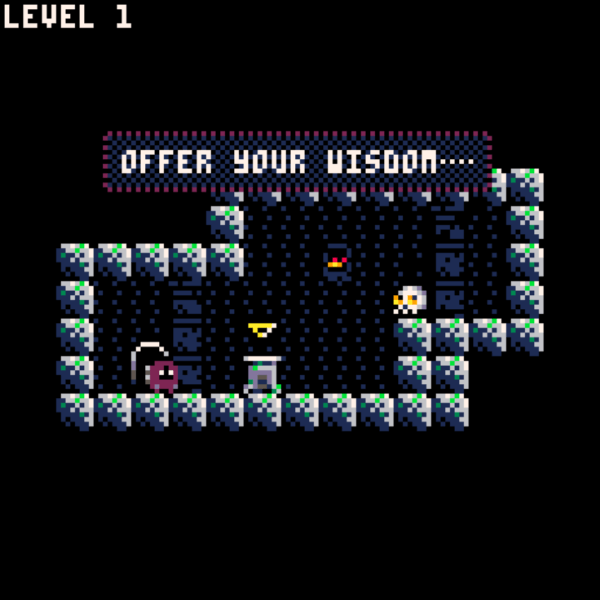

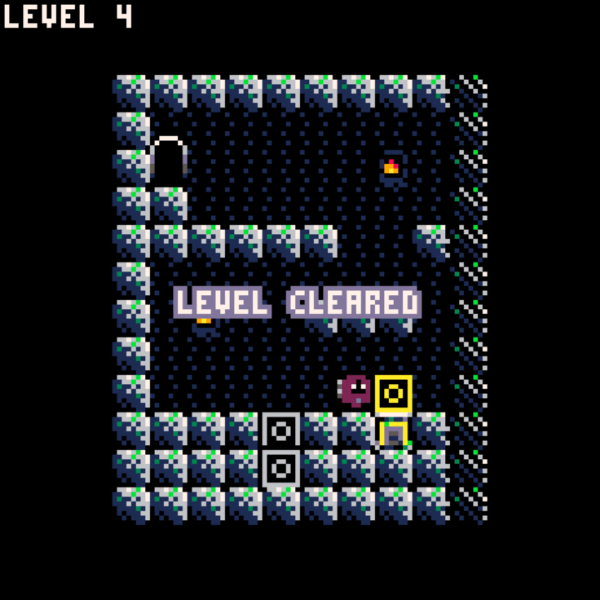

Magicube is strictly a puzzle game. It looks like a puzzle-platformer at first glance, but at no point will your platforming skills be put to the test. Your puzzling skills, however, are another matter entirely. The tutorial quickly and efficiently explains things: how to move, jump, push blocks around, and chant a spell to summon a single magical cube. Your goal is to place the titular magicube upon a pedestal. Simple. But far from easy.

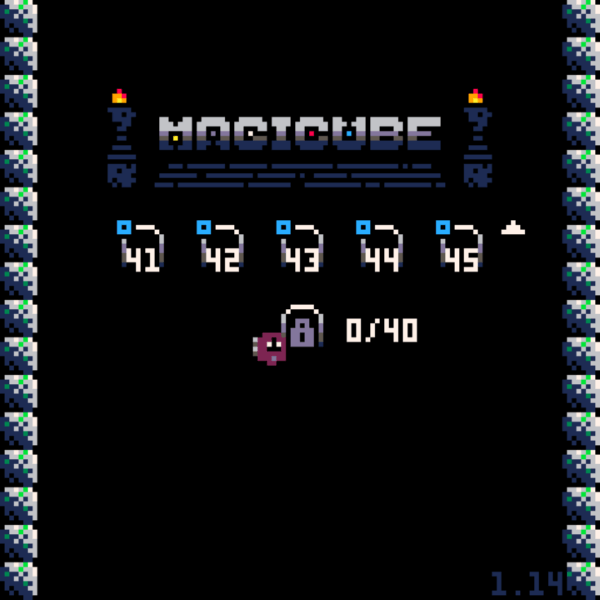

Magicube’s simplicity belies its fiendish difficulty. Like many classics of the genre, after the first two or three levels help you find your feet, the game immediately stops holding your hand and starts unleashing some very tricky puzzles—and this is when it really got its hooks into me. The vast majority of its fifty puzzles are extremely difficult.

The game’s simple core has some interesting emergent behaviours, and many of the early puzzles require you to discover these behaviours yourself. These discoveries will then be key to solving later puzzles. Most of the levels are available to you from near the start of the game, so you can approach them in whatever order you like, and often beating one level will lead to an “aha!” moment that sends you scurrying away to another level that previously had you stumped. This kind of scaffolded puzzle design—in which the solutions to some puzzles are themselves hints to solving other puzzles—is not unique to Magicube, but the subtlety of doing this correctly is a very understated skill. None of the levels feel like tutorials preparing you for the real game; they’re all a proper challenge in their own right.

And of course, like many great puzzle games, just when you feel like you’ve finally gotten the hang of things, Magicube is quick to surprise you. It starts introducing new elements: laser beams, buttons, disappearing blocks, transparent blocks, and so on. And of course, once you get the hang of these new elements, there are puzzles that combine them. If you’ve played a lot of thinky games, you’re probably familiar with this concept , but the care and thought that has clearly been put into designing these puzzles makes the whole thing feel very smooth and natural.

Steam tells me I have spent over 160 hours playing Magicube, and I still have a couple of puzzles left unsolved. But probably less than 10% of that time was spent with a controller in my hands. Because the basic rules are so simple, and because every puzzle in the game fits on a single, small, PICO-8-sized screen, you can generally keep the gist of it all in your head. It’s the kind of game you’ll be ruminating over for hours throughout the day, with some small part of your mind pondering the puzzles in the background. It taps into the same part of the brain that loves chess puzzles, sudoku and crosswords.

As for the time spent with a controller in hand, Magicube performs perfectly well, with smooth and responsive controls. Manoeuvring your character through the level is never part of the challenge. Within a few minutes of playing, it becomes obvious that clearing any particular jump is either easy or impossible, never difficult. There’s also a generous undo feature to rewind steps as far as you like, just in case things simply don’t work out like you expected.

There has been more than enough discussion in gaming circles over the last few years about the merits of difficulty in games, and how this should or shouldn’t be tempered with accessibility options. In that regards, Magicube should be considered a triumph in accessibility. Its extremely forgiving controls let anyone enjoy its merciless puzzle design… provided that they find brutally challenging puzzles enjoyable. But if you do like brutally challenging puzzles—if you like games that make you feel smart, not through subtle psychological tricks, but through presenting you with legitimately difficult problems and leaving you to solve them with nothing but your own wits to aid you, then give Magicube a shot. Every time you beat one of its fiendish little puzzles you’ll feel like a genius.

Magicube is currently out on Steam. Visit nebu soku’s itch page for even more of their puzzle games. And you can watch Indie Tsushin play Magicube on stream!